Deep Life Reflections: Friday Five

Issue 152 - Nighthawks

Welcome to Issue 152 of Deep Life Reflections, where each Friday I share reflections on how to live more deeply—through literature, cinema, and the everyday strands of life.

“If you could say it in words there would be no reason to paint.”

— Edward Hopper

In my early twenties, I spent six months living in America. It was some early work experience and my first time experiencing the expansiveness and scale of the country. I was based in the port city of Cleveland, Ohio, which sat on Lake Erie. During my stay, I had the opportunity to visit other U.S. cities like Chicago, San Francisco, and New York. I still have the photos in a physical album, as well as a few mementos like postcards and maps. Being there myself, I was often alone in both my travels and daily comings and goings. Not all the time, but most of the time.

I think this is why the art of the American realist painter, Edward Hopper, struck a chord then and continues to now. Hopper specialised in painting American solitude. Aloneness was his great theme. Hopper had two primary sources for his subject matter. The common aspects of American life, such as restaurants, theatres, motels, gas stations, and railroads, and the people who inhabited them. His most common subject was the solitary figure, and they were mostly women, often reading or looking out of a window. Many of his solitary women were modelled by his wife, Josephine, herself an artist.

Best known for his oil paintings, Hopper had a mastery of light and shadow, together with a gift of seeing into the inner soul of a society still finding its own sense of self. While many interpret loneliness and isolation in his works—and it would be hard to discount a veil of melancholy in many of those pieces—some critics see this loneliness and isolation differently, more as a symbol of Hopper’s preference for quiet and thoughtful self-examination and contemplation. That’s the way I look at them too.

Hopper was born in a small town called Nyack, New York, in 1892. Moving to the city in 1908, he lived for half a century in a modest fourth-floor apartment on Washington Square in Manhattan, until his death in 1967. Even in his old age, Hopper carried buckets of coal up the four flights of stairs for the stove that heated his studio. He lived a somewhat frugal life, enjoying inexpensive diners that reflected the changing fabric of the city.

New York was his canvas. Disregarding the city’s world-famous skyline and its iconic sights like the Brooklyn Bridge and Empire State Building, he instead turned his gaze to the more overlooked vistas and the interiors of daily life: the apartment, the café, the movie house. He had an enduring fascination with windows and theatre scenes. He blended the public and the private, connecting the person and place. In doing so, he captured both the unique and neglected aspects of his city, giving them voice and recognition. Hopper once said:

“In general, it can be said that a nation’s art is greatest when it reflects the character of its people.”

Hopper’s own character was reflected in his work. He was a tall man at 6 feet 5 inches. By age 12, he had already reached 6 feet. His height and gangly physique earned him the nickname ‘Grasshopper’ and it contributed to his growing sense of isolation and loneliness, and his individualist mindset.

His art took around two decades to take the form we recognise today. As a young boy, he discovered English classics and French and Russian translations in his father’s library. Highly literate, he read and re-read nineteenth-century German and French poetry all his life. As well as literature, Hopper was also a lover of film and theatre. He once said, “When I don’t feel in the mood for painting, I go to the movies for a week or more.”

Always reluctant to discuss himself and his art, Hopper simply said, “The whole answer is there on the canvas.”

If we look at the canvas today, we see art that is timeless, or as The New Yorker said, “perhaps time-free.” Because Hopper has given us a series of freeze-dried moments. Of normal places we inhabit daily. Of people who are perhaps in a predicament or alone or feel restless or unsure, but have decided to go on regardless.

And so these moments, these works, become telling. Hopper drew deeply from his imagination and his insights into the human psyche and was able to distil life to its very foundation: to be seen and to be understood.

To matter.

Below I have selected five of my favourite Edward Hopper paintings. They all remind me of both my time in America three decades ago and all that has come since.

I’d be interested in what you see.

Five Works by Edward Hopper

AMERICAN REALIST PAINTER, 1882-1967

New York Movie (1939)

A near-empty movie theatre with a few patrons and a contemplative usherette lost in her own thoughts. The lighting is rich and sophisticated, highlighting the suggestion of female isolation. She’s not really watching the film. She is in her own story.

The House by the Railroad (1925)

Alfred Hitchcock acknowledged the influence of Hopper’s 1925 painting in his creation of the Bates house in his 1960 film Psycho. Ominous in its normalcy, Hitchcock clearly picked up on its presence as a representation of something not quite right despite having all the pieces.

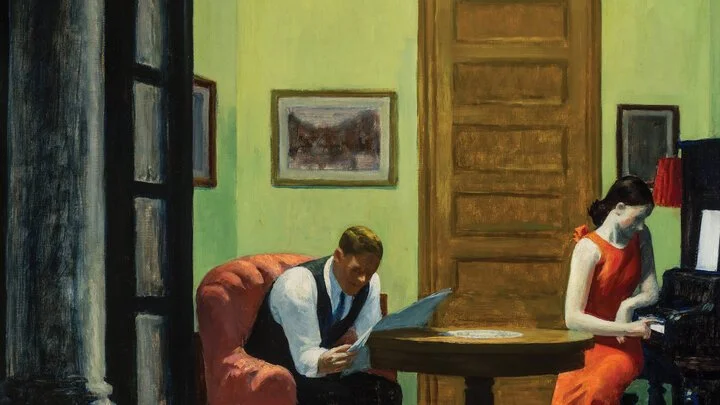

Room in New York (1932)

Hopper captures urban loneliness here. Two people in the same room but in different worlds, where perhaps a lack of communication or intimacy has created a sense of intentional withdrawal into the inanimate: the newspaper and the piano.

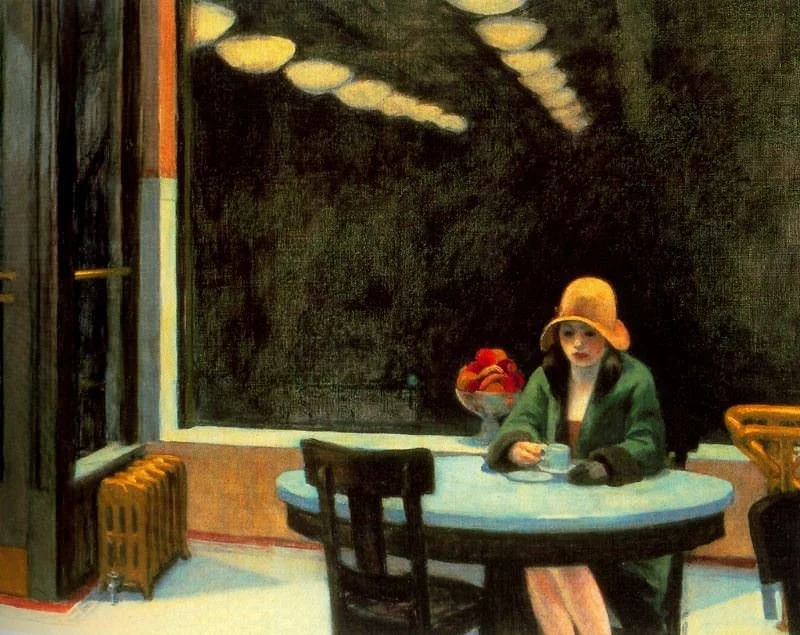

Automat (1927)

As is often the case in Hopper’s paintings, both the woman’s circumstances and her mood are ambiguous. She sits alone, one glove off, gazing at her coffee as if it were the last thing in the world she could make sense of. Hopper’s wife, Josephine, served as the model.

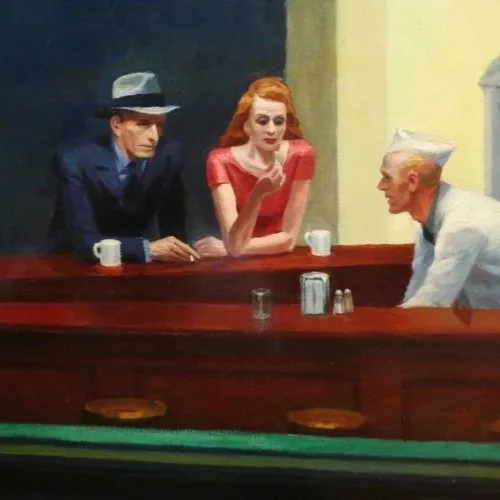

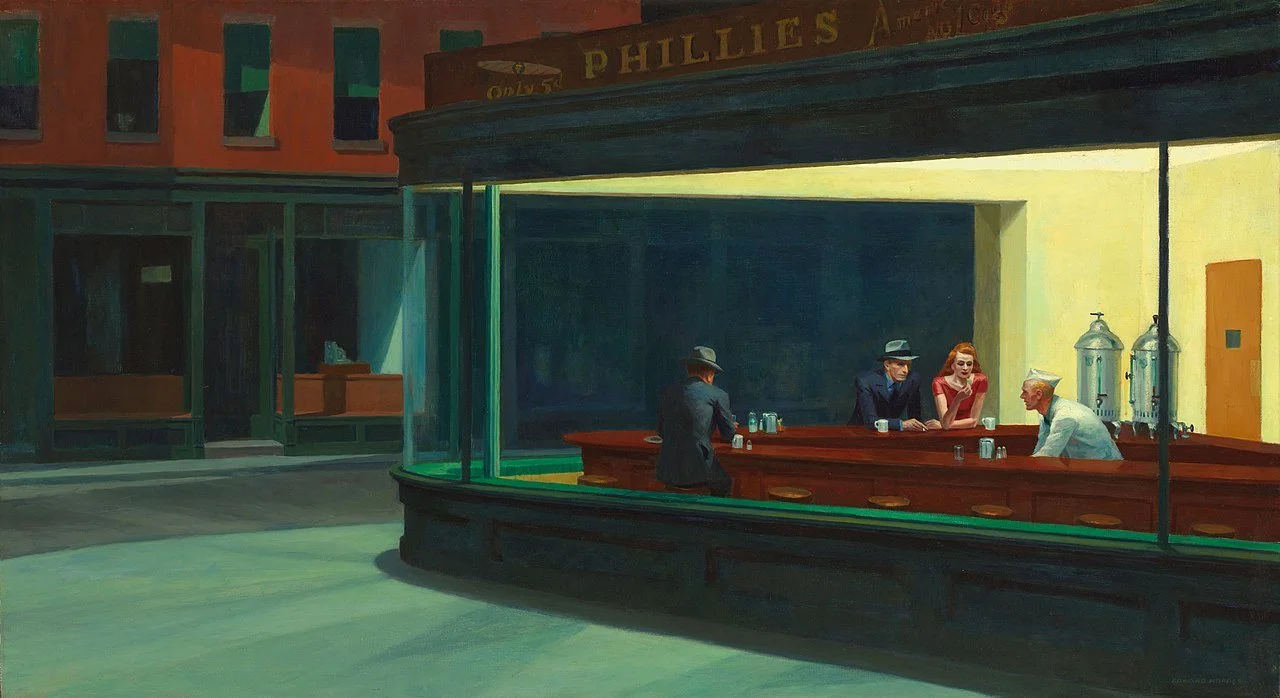

Nighthawks (1942)

Hopper’s most famous work. In response to a query about loneliness and emptiness in the painting, he said he “didn’t see it as particularly lonely.” Then added: “Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.” Most of us I suspect recognise this view at certain times of our life.

A Question for you

If Hopper painted a scene from your life this week, where would he place you and who would be watching?

Thanks for reading and reflecting. As always, I’d love to hear any thoughts you may have. You can leave a comment here or drop me a line.

Pass It On

Deep Life Reflections travels best when it’s passed hand to hand.

If you know someone who might enjoy it, feel free to share this issue with them:

👉🏻 https://www.deeplifejourney.com/deep-life-reflections/13-february-2026

Or, if you’d like to invite them to join directly, here’s the subscription link:

👉🏻 https://www.deeplifejourney.com/subscribe

You can read all previous issues of Deep Life Reflections here.