Deep Life Reflections: Friday Five

Issue 141 - Speck

Tomorrow, I turn 50.

I’m not quite sure how that happened.

Once a year, Deep Life Reflections falls on or close to my birthday. This year, on Issue 141, it comes the day before.

Last year, I shared 49 observations from 49 years of life. This week, I re-read them. They hold up. #37 said:

“Don’t aim for happiness—it’s fleeting and we can’t control it. Instead, aim for fulfilment. We’ve got a better shot there.”

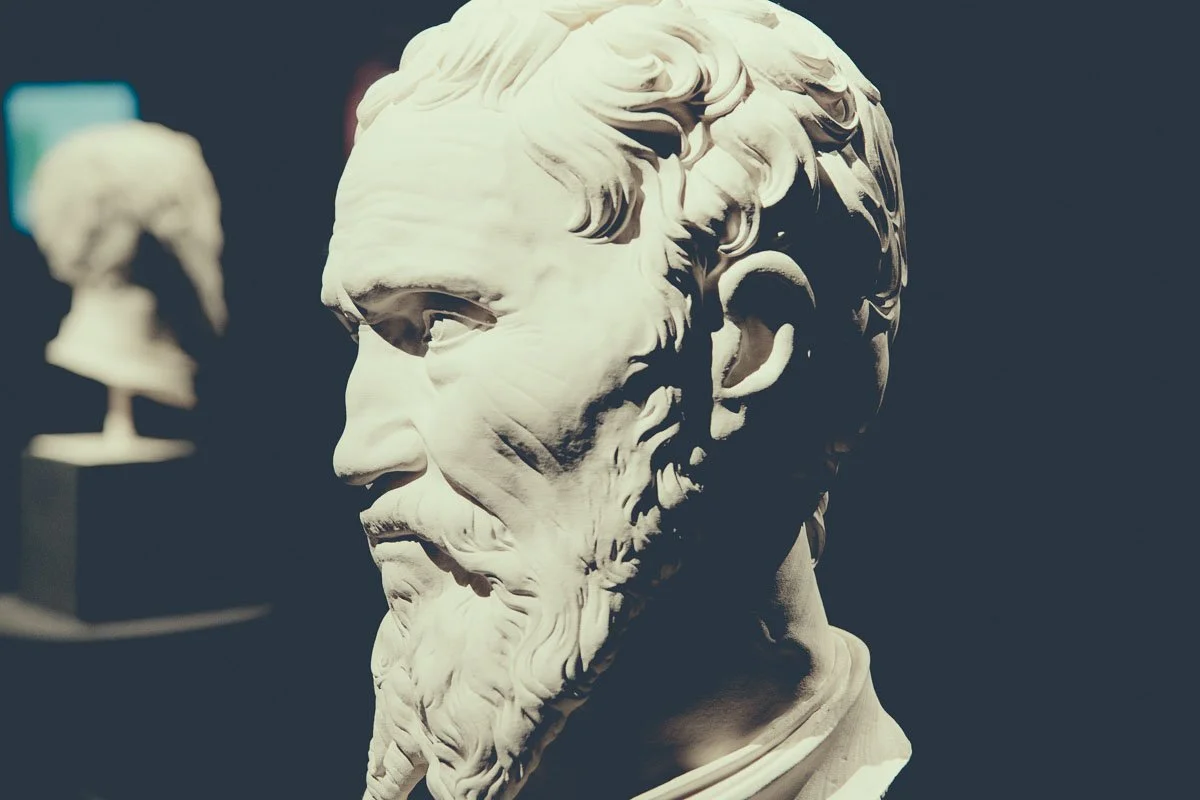

Living well has always interested me. And on the eve of half a century on the planet, I happened across the writings of Carl Jung, a man who knew a thing or two about the human psyche and the art of living.

The Swiss psychologist, who gave us terms like introvert, persona, and archetype, once wrote:

“Happiness is such a remarkable reality that there is nobody who does not long for it. And yet there is not a single objective criterion which would prove beyond all doubt that this condition necessarily exists.”

Jung is pointing to something important: the kind of happiness we chase—permanent, all-consuming, guaranteed—is a myth. Life, by its very nature, is volatile, prone to swells and plunges, calm stretches and sudden storms. Happiness can’t be pinned down. It’s like the perfect slice of chocolate cake sitting on the third shelf of the fridge. Briefly there, then gone.

But that doesn’t mean we abandon the search.

Jung was once asked:

What do you consider to be the basic factors for happiness in the human mind?

He offered five. Essentially Jung’s blueprint for a meaningful life.

Good physical and mental health

Good personal and intimate relations, such as those of marriage, the family, and friendships.

The faculty for perceiving beauty in art and nature.

Reasonable standards of living and satisfactory work.

A philosophic or religious point of view capable of coping successfully with the vicissitudes of life.

Today seems a good day to take a closer look.

Join me for this week’s Friday Five.

On Turning 50 and Living Well

(With A Little Help from Carl Jung)

1. Good physical and mental health

We often treat health as something we notice only when it goes wrong. As the saying goes, “You can have a thousand problems… until you have a serious health problem. Then you only have one.”

I faced this myself two years ago almost to the day when I was told I needed open-heart surgery to replace a damaged heart valve.

If Jung is right, and happiness requires certain baseline conditions, then good health is one of them.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development, now in its 80th year, identified four major predictors of wellbeing in later life: don’t smoke excessively, drink moderately (if at all), maintain a healthy weight, and stay physically active. Pretty unremarkable advice until you realise how few people follow it consistently.

Mental health may matter even more. A 2013 study comparing Britons, Germans, and Australians found that poor mental health was two to six times more predictive of misery than poor physical health. That’s a big margin.

In other words, good health doesn’t necessarily create happiness. But poor health, especially mental, reliably erodes it.

We often think of happiness and unhappiness as opposites. But research suggests they’re not. They operate independently. Which means a good life is just as dependent on managing the lows as chasing the highs. Protecting the floor beneath us.

Good health may not guarantee happiness. But it gives us our best shot at staying upright when life throws its inevitable punches.

2. Good personal and intimate relations, such as those of marriage, the family, and friendships

“Good relationships keep us healthier and happier. Period.”

That’s how Robert Waldinger, director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, summarises eight decades of research. And the data backs him up: rich, stable connections with family, partners, and close friends are among the strongest predictors of long-term wellbeing.

The benefits aren’t just emotional. Healthy interactions reduce stress, sharpen memory, and boost cognitive performance. Taking part in meaningful conversations, exchanging ideas, and participating in group activities keeps the brain alive and engaged.

But we’re living through what some call a loneliness epidemic. Others dispute the term, pointing instead to rising solitude. The two are not the same. You can feel lonely in a crowded room and perfectly at peace alone in the woods. Loneliness is less about proximity and more about resonance—feeling understood, valued, and cared for.

That kind of connection doesn’t happen by default. It requires depth, reciprocity, and intentionality.

Modern life doesn’t make it easy. Urbanisation, remote work, individualism, and the ever-expanding presence of digital devices have reshaped how we live the minutiae of our lives. The algorithms of social media are winning at the moment. In every public place, everyone’s staring at a screen. But there is no algorithm for intimacy.

We have to choose it.

Jung did. He was married to his wife, Emma, for 52 years, until her death at 73. In his work and life, he understood that the psyche doesn’t thrive in isolation. It’s shaped and steadied by those we hold close.

3. The faculty for perceiving beauty in art and nature

A few years ago, while camping in the Arabian desert, I took several steps beyond my tent, up and over a nearby sand dune. It was pitch black. Midnight. Absolutely silent. When I looked up, the sky was a blanket of stars. Even if I’d had my camera, only my eyes could have done it justice.

This is the kind of beauty Jung meant. Research shows that engaging with the natural world increases wellbeing. People feel more grounded, more connected to nature. It transcends culture or geography. It’s universal.

Beauty reminds us of our smallness. That we are a speck on a speck. And that’s a good thing.

Self-preoccupation often makes us anxious. There’s a fine line between healthy self-respect and compulsive self-performance. The modern obsession with self-congratulation and the quest to be noticed, to make ourselves bigger, often backfires. The downside of success is that it can magnify our insecurities.

But awe shrinks the ego. Nature, art, music, books, they all pull us outside of ourselves. And in that smallness, we often find peace and perspective.

We are tiny. Cosmically irrelevant. But loved by a handful of other tiny people. And that’s enough.

4. Reasonable standards of living and satisfactory work

I’ve never been convinced by the phrase “Do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life.” If only it was that simple.

Most people don’t get that luxury, but most still want to feel their work means something, and that their efforts give them enough to live without constant financial anxiety. Decades of research show that few things impact wellbeing faster than unemployment or never-ending financial stress.

Jung, interestingly, downplayed work’s role. His word was “satisfactory”—a fairly muted benchmark. But work has changed in the sixty years since his death. As I’ve written before, work has become the cornerstone of identity for many people.

Career has taken on the weight once reserved for religion or community. We don’t just do our jobs. We are them.

Two themes consistently make work feel purposeful: earned success—the sense of accomplishing something valuable—and service to others, which can be found in almost any role.

The relationship between money and happiness remains contentious. But a few things are clear. It’s better to have money than not have it—at least to cover basic needs and reduce daily stress. Beyond that, accumulating more possessions rarely makes us happier. Instead, we can be happier by using money to buy time, create freedom, and share experiences with the people we care about.

It’s also worth remembering that the typical person gets about 4,000 weeks of life. Of that, only around 3,000 are waking and conscious. And work makes up just one-sixth of that time.

So yes, work matters. And ideally, it’s purposeful. But it’s not everything.

Perhaps that’s what Jung was getting at.

5. A philosophic or religious point of view capable of coping successfully with the vicissitudes of life.

Jung, the son of a pastor, was deeply Christian in his worldview. But he didn’t insist religion was the only path. What he did believe was that everyone needs some kind of framework—something larger than themselves—to make sense of life, especially when it falls apart.

I’ve never belonged to a particular religion. But I’ve visited many churches, mosques, temples, and sacred sites around the world. I’ve always found them architecturally impressive as well as peaceful and reflective. They offer a kind of sanctuary. A place to retreat from whatever challenges someone may be facing; a return to something older and deeper.

Research shows that both religious belief and spirituality are linked to better mental health. But secular philosophies can serve the same role. Stoicism for example is an ancient system built on discipline and perseverance. Its four virtues—Courage, Temperance, Justice, and Wisdom—offer a structure for living meaningfully, especially in difficult times.

Whatever the system, the point is the same: life is unpredictable. It will bend us. Sometimes it will break us. What matters is whether we have a view of the world that can help us hold the ship steady—and begin again when the waters settle.

Final thoughts

Jung made this list to mark his 85th birthday. It was the last one he celebrated. He died with a sense of peace, confident he had used his gifts in service of something larger than himself.

That possibility isn’t reserved for the old or the wise. It’s open to all of us, at any age. As the saying goes: you’ll never be younger than you are right now.

Jung’s list isn’t definitive. But it shows that even the smallest life, lived with care, connection, and service, can leave a lasting mark.

We may be specks. Brief and small in the grand scheme.

But we’re here.

And we get to decide what that means.

A Question for You

Which of Jung’s five pillars do you feel strongest in right now—and which one might need more of your attention?

Thanks for taking this reflective journey with me this week. As always, I’d love to hear any thoughts you may have. You can leave a comment here or drop me a line.

📸 All the images used this week are my own photographs, taken in South Africa, Iceland, Italy, Sweden, and Japan.

Pass It On

Thanks for reading and reflecting. If you enjoyed the issue, please leave a comment below. I’d love to hear.

Deep Life Reflections travels best when it’s passed hand to hand.

If you know someone who might enjoy it, feel free to share this issue with them:

👉🏻 https://www.deeplifejourney.com/deep-life-reflections/28-november-2025

Or, if you’d like to invite them to join directly, here’s the subscription link:

👉🏻 https://www.deeplifejourney.com/subscribe

You can read all previous issues of Deep Life Reflections here.