Deep Life Reflections: Friday Five

Issue 150 - Raiders

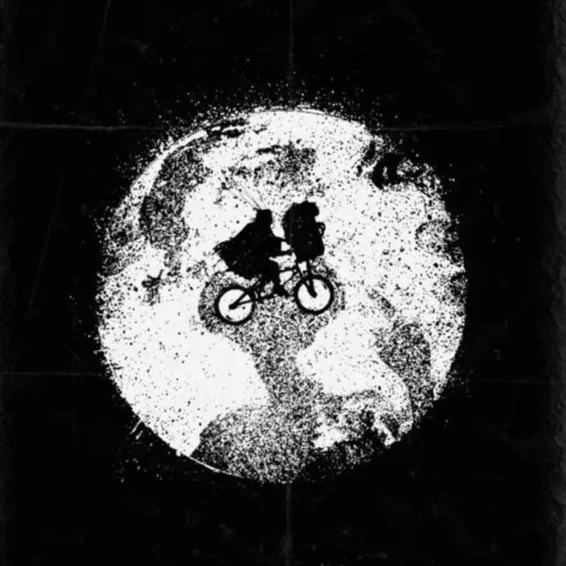

Earlier this week, I listened to one of my favourite podcasts, All The Right Movies. It was a special two-part feature on the films of Steven Spielberg, ranking his ten best movies. Just even getting it down to a shortlist of ten was hard enough. Spielberg has directed more than 35 feature films in his career, winning 217 awards, including three Oscars. He made his debut at twelve years of age in 1959 with the short feature The Last Gun.

In the end, this is how they settled on Spielberg’s top five films, in reverse order:

5. Jurassic Park (1993)

4. Saving Private Ryan (1998)

3. Schindler’s List (1993)

1.= Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

1.= Jaws (1975)

Raiders and Jaws couldn’t be split. A tie. I don’t think I could split them either.

Behind Spielberg’s greatness is his devotion to the slow. To the failure-prone process. He was 27 years old when he made Jaws, directing a cast and crew of over a hundred people, including seasoned lead actors. He took his cameras to the unpredictable and choppy waters around Martha’s Vineyard. The shark wouldn’t work. There were reshoots, compromises, and in Robert Shaw, a flamboyant actor who needed a minder to keep him sober off set (it didn’t work). Spielberg called the whole thing “a living nightmare.”

Yet, Jaws changed cinema forever.

Craft was the cost of movie magic. The friction, the discipline, the attention, the mistakes, the frustrations, the joys. That’s the labour of craft. A very human labour. A noble labour.

This week marks 150 editions of Deep Life Reflections. Whether you’re a recent new reader or someone who has been here since the start, my thanks for your support.

A hundred and fifty issues can be seen as an example of craft. It can also be seen as an example of discipline, labour, and struggle. Discipline, labour, and struggle are where craft is often forged. They are not the only ingredients, but they are three essential ones.

But craft, if not understood properly, can also become a cage. That jars me slightly as I write it, because I have always seen craft as something 100% positive. Craft as a cage is a new thought for me. And it’s something I’ve been thinking about recently.

Craft has always been one of my guiding principles behind a good life. I don’t think of craft just in terms of creative output, like writing or painting or filmmaking. It’s much broader.

Craft is how you approach anything that matters. It’s the deliberate shaping of anything that carries your name.

Craft is visible across many areas of our lives:

Craft in Leadership (the standards you hold)

Craft in Relationships (how you listen and choose your words)

Craft in Health (the way you cook, exercise, and recover)

Craft in Parenting (the tone you take and behaviours you model)

Craft in Career (the reputation you earn)

Craft can be a guiding principle, but there are hazards to be aware of. They revolve around identity, legacy, and accumulation.

If we start to think “I am my output,” there is a clear breach in our identity. We become the output, which means if the output stops or there is a decline in quality, we equate that to a lowering of our identity or self-esteem.

A second danger is legacy thinking—the itch to matter, to leave something worthwhile behind to the world. It’s interesting that Sigmund Freud, who gave so much to the world through psychoanalysis, also seemed deeply concerned with how history would remember him. Founders often are. The desire to contribute can become the all-consuming desire to be remembered. And sometimes the price of that desire is paid far beyond the individual.

Then we have the common addiction to “more”, the accumulation problem. When we have 150, we must hit 200 next. Then 500. Then 1,000. That creates output anxiety and a subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) shift towards creating something that is performative rather than real. I can’t imagine where we see that today.

Craft is very much a balance. If we were to find a formula it might be something like:

Craft = expression without accumulation.

If I were to apply this formula to myself in practical terms, I would offer the following antidotes when it comes to writing:

Create more than I publish.

Leave some work unfinished on purpose. (That’s a difficult one)

Embrace seasonality. Spend more time reading than writing in some months.

I’d also ask the question: “Would I still do this if no one ever saw it again?”

Perhaps that’s a question you might also ask yourself in a particular part of your life right now.

All of this is to say craft is important. It gives us meaning. As human beings, we derive great satisfaction from shaping and accomplishing things that matter in our lives, whether we paint, run, cycle, raise children, ride horses, build businesses, or solve mathematical riddles.

We should keep making.

But release the grip a little on what we make.

Craft should shape us. Not own us.

A final thought before you go.

We have entered an age that promises creativity without friction. The CEOs of the big AI companies describe a future world of creativity without craft. In their framing, execution is the bottleneck. Remove the friction and we unleash human potential. Describe the idea and the machine will do the rest.

But friction is not a bottleneck. It’s where craft forms. It’s also where judgment, struggle, and meaning are formed. Remove the labour and yes, you may increase output, but you hollow out the experience of being a maker. You also flood the world with cheap, shallow, attention-grabbing “art” that is optimised for speed and scale rather than depth and deliberation.

Craft is slow. It requires sustained attention. It demands revision, failure, patience, time. It builds taste and competence. It also builds humility. That’s how humans assert themselves in the world. We need the friction to retain our humanity.

Without craft, we risk a thinning of culture and a subtle personal loss as we move away from the friction and hard labour of creation and towards the obsession with how quickly we can produce something, anything, and who we become in the act of producing it.

And that leads to a final question:

Where do the next Jaws and Raiders come from?

And by whom?

Pass It On

Thanks for reading and reflecting. If you enjoyed the issue, please leave a comment below.

Deep Life Reflections travels best when it’s passed hand to hand.

If you know someone who might enjoy it, feel free to share this issue with them:

👉🏻 https://www.deeplifejourney.com/deep-life-reflections/january-30-2026

Or, if you’d like to invite them to join directly, here’s the subscription link:

👉🏻 https://www.deeplifejourney.com/subscribe

You can read all previous issues of Deep Life Reflections here.