Deep Life Reflections: Friday Five

Issue 139 - Rosebud

Is there a single word that explains your life? Would it be enough?

Welcome to Issue 139 of Deep Life Reflections, where each Friday I share reflections on how to live more deeply—through literature, cinema, and the everyday strands of life.

This week, we examine the self through a bestselling book of patient stories from the consulting room couch and one of the greatest films ever made—whose director, like his character, was prodigious, newsworthy, and frequently misunderstood.

Join me as we explore this week’s Friday Five.

1. What I’m Reading

The Examined Self. By Stephen Grosz.

Amanda, a 28-year-old single woman, returns home to London after a business trip to New York. She lives alone. As she turns the key to her front door, a fantasy takes hold. She imagines terrorists have got into her home and planted a bomb to kill her. She visualises it like a film. Turning the key triggers a detonator and in a split-second the whole place goes up in a firestorm, the door exploding off its hinges, killing her instantly.

“Why would I have such a crazy fantasy?” she asks.

This is one of many patient stories shared with London-based psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz featured in his 2013 book, The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves. Grosz presents a series of short case studies that reveal the mysterious lives we lead and the stories we tell ourselves.

The stories are often strange, a little dark, almost fablelike. There is the 72-year-old professor who says he can’t be fixed: that he’s lived his whole life as a lie. There’s Phillip, a pathological liar who makes up stories so absurd that he seems to sabotage himself willingly. And then there’s Peter, a structural engineer and high-risk (suicidal) patient.

Grosz saw Peter for six months before he stopped coming. Two months later Grosz received a letter from Peter’s fiancée saying he’d taken his own life. Grosz wrote a letter of condolence. It affected him. Six months later, Grosz received a message on his answering machine. Peter’s voice. “It’s me. I’m not dead. I was wondering if I could come and talk to you.”

Grosz categorises his patient stories—which have all been modified for confidentiality—under broad themes: lies, loving, leaving, and change. Change is constant. Grosz recalls a patient saying to him, without irony: “I want to change, but not if it means changing.” Grosz recognises that loss is deeply connected to change. There cannot be change without it. This theme seeps through almost every patient tale Grosz recounts.

Each story is only a few pages long and often doesn’t end with neat resolutions, reflecting the conundrum of analysis, and the wider enigmas of the heart and mind. Grosz doesn’t always have an answer, or at least, he needs to know more. Analysis is a long, complicated process with unreliable characters. There are walls to be scaled, walked around, or removed.

Dreams are recurring themes in the patient stories, and therapeutic breakthroughs often happen after Grosz and the patient analyse a dream. His patients frequently trace the origins of their issues to early childhood, to a dead or emotionally absent parent. Dreams are where our stories live. Grosz explains:

“When we cannot find a way of telling our story… when we feel trapped by the things we find ourselves thinking or doing, imprisoned by our own history and beliefs… our story tells us — we dream these stories, we develop symptoms, or we find ourselves acting in ways we don’t understand.”

Returning to Amanda’s story—her paranoid fantasy about being blown up by terrorists—the question she asked wasn’t so crazy after all. While the fantasy frightened her, ultimately this fear saved her from feeling alone. The thought ‘someone wants to kill me’ gave her an experience of being hated. But not forgotten. She existed in the mind of the terrorist. Her paranoia shielded her from the catastrophe of indifference. (I wrote about this existential fear two weeks ago.)

Loss haunts this book. Even when you win, you lose something.

Yet, for all the pain, confusion, grief, and complexity of these stories, we are given the rare privilege of sitting in. Watching someone listen, understand, and acknowledge another human being. Helping them figure out the challenge of living.

To examine that life, even just a little, is to honour it.

2. What I’m Watching

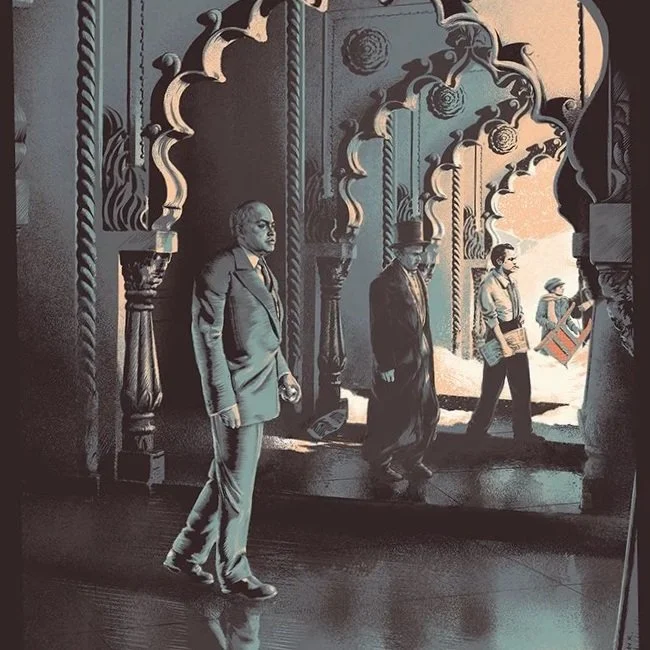

Citizen Kane. (1941). Directed by Orson Welles.

“Mr. Kane was a man who got everything he wanted and then lost it. Maybe Rosebud was something he couldn’t get, or something he lost. Anyway, it wouldn’t have explained everything… I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life. No, I guess Rosebud is just a piece in a jigsaw puzzle… a missing piece.”

Charles Foster Kane left behind a story. His story. But no one, not the journalists, his friends, his lovers, or those who knew him best, could make sense of it. Perhaps only Kane truly knew it. But I don’t think he did.

Citizen Kane transformed Hollywood after its release in 1941, bringing a cinematic language, storytelling, and technical craft that hadn’t been seen before—and would go on to shape the next 80 years of film. In 1998, the American Film Institute polled 1,500 film professionals and Citizen Kane topped the list. Ten years later, the AFI ran another poll. It retained top spot. Film critic Kenneth Tynan wrote, “Nobody who saw Citizen Kane at an impressionable age will ever forget the experience.” I wouldn’t disagree.

I first saw the movie in the Glasgow Film Theatre in the winter of 1998 with my friend Gavin. We walked out in silence. We knew we’d seen something special. The power and legacy of the film still resonate more than a quarter of a century later.

The film tells the story of Charles Foster Kane, a newspaper tycoon from humble origins who amassed a great fortune and influence in American society. On his deathbed, he utters a single final word: “Rosebud.” A reporter, Thompson, is sent to speak to those who knew Kane best, to try and find out who or what Rosebud was or is. They want a story to explain the man. “Find Rosebud and we find the man,” the editor tells his team. “It’ll probably turn out to be something very simple.”

The story unfurls through the memories of others, recollections of Kane that span a half century. We see these as a series of flashbacks. As questions are answered, new questions are raised. We go back and forth, from his youth to middle age to eventual isolation, his newspapers, his wives, his political ambitions, his principles, and his follies. And his hubris.

“There’s only one person in the world who’s going to decide what I’m going to do and that’s me.” — Charles Foster Kane

One of the pleasures of rewatching Citizen Kane is you can never remember what scene comes next. It remains fresh and vivid, unconventional, always something new to pick up on; another appreciation of the camera wizardry or the immaculate photography by Gregg Toland, considered the best cinematographer in the world at the time. Toland showed up one day and was reported to have said, “My name’s Toland and I want you to use me on your picture. I want to work with somebody who never made a movie.”

That somebody is Orson Welles. The story of Citizen Kane is also the story of Orson Welles. A brash prodigy of stage and radio, Welles marched into Hollywood at the age of 25 with an unprecedented contract of a three-picture deal, a massive budget, and final cut of his first film—almost unheard of. It was a huge gamble by RKO Studios.

Welles loosely based the character of Kane on William Randolph Hearst, one of the most powerful men in the world. Hearst, upset with the portrayal, laid his full wrath upon Welles and RKO Studios. All this created a massive wave of publicity for the film, but the film was blacklisted in major papers owned by Hearst.

While the film was nominated for 13 Academy Awards, it won only one (Best Writing, Original Screenplay) and was booed each time its name was mentioned as a nomination. Welles would later remark almost Kane-like, “If Hearst isn’t rightfully careful, I’m going to make a film that’s really based on his life.”

That lone Oscar was well deserved. Welles had brought in veteran satirist and hard-drinking screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz as his co-writer. Mankiewicz gave us dialogue like this:

“A fellow will remember a lot of things you wouldn’t think he’d remember. You take me. One day, back in 1896, I was crossing over to Jersey on the ferry, and as we pulled out, there was another ferry pulling in, and on it there was a girl waiting to get off. A white dress she had on. She was carrying a white parasol. I only saw her for one second. She didn’t see me at all, but I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since I haven’t thought of that girl.”

(Mr. Bernstein, Kane’s long-time business manager)

Citizen Kane may explain what Rosebud is, but not what Rosebud means. The way the film tells Kane’s story shows how, once we’re gone, our lives survive only in the memories of others, prone to distortion, exaggeration, or, worse, disappearance.

Kane’s life is examined, but remains a puzzle even after the pieces are laid out.

Not every life can be understood. Even ones like Charles Foster Kane.

3. What I’m Contemplating

Some years ago, I read Citizen Welles, a biography of Orson Welles. I learned he’d gone to Dublin, Ireland, at just fifteen, talked his way onto the stage, and held his own among established adult actors. By twenty, he was a star of Broadway. Then he was given the keys to Hollywood, or as he described it, “the biggest electric train set a boy ever had.”

Welles was audacious. Certainly a genius. He didn’t wait to be invited. And now he had a third medium to conquer.

But for all the genius (and eventual acclaim) of Citizen Kane, Welles never again sat at that pinnacle of greatness in Hollywood. His next film, The Magnificent Ambersons, was butchered, re-edited with a ‘happy’ ending by the studio. He disowned it. Still, it’s considered one of the great works of American cinema.

On his next film, It’s All True, a documentary in Brazil, Welles was fired by the studio for allegedly going over budget. The same journalists who had once praised him now dismissed him as arrogant and overblown.

Did Welles rise too fast?

Though Welles would go on to direct twelve more films—called by one critic as twelve of the greatest films ever made—he never quite found his way back to the place he started. If he still had the keys, they no longer opened the same lofty doors.

Some critics called him a failure. That seems absurd. It’s a strange thing. How we punish early brilliance if it doesn’t evolve the way we expect.

Welles died in 1985. There was no final act, no Hollywood redemption arc.

Like his most famous character, Charles Foster Kane, Welles is remembered now though the memory of others. Kenneth Tynan placed him alongside Chaplin, Ellington, Picasso, and Hemmingway. Woody Allen called him “the only American director.”

The years have been kinder to Welles in the four decades since his death. History creates new voices. And new perspectives. Younger audiences discover works like Citizen Kane. And the stories behind it.

A reminder that a life—even one no longer physically here—can still evolve.

4. A Quote to note

“I run a couple of newspapers. What do you do?”

- Charles Foster Kane

5. A Question for you

What’s one piece of your story, however small, that still shapes who you are?

Pass It On

Thanks for reading and reflecting. If you enjoyed the issue, please leave a comment below.

Deep Life Reflections travels best when it’s passed hand to hand.

If you know someone who might enjoy it, feel free to share this issue with them:

👉🏻 https://www.deeplifejourney.com/deep-life-reflections/november-14-2025

Or, if you’d like to invite them to join directly, here’s the subscription link:

👉🏻 https://www.deeplifejourney.com/subscribe

You can read all previous issues of Deep Life Reflections here.