Deep Life Reflections: Friday Five

Issue 128 - Paradise Lost

What if the difference between good and evil is not who we are, but where we are?

Welcome to Issue 128 of Deep Life Reflections, where each Friday I share reflections on how to live more deeply, inspired by literature, cinema, and life itself.

This week, we explore the shifting line between good and evil, and how almost anyone can be persuaded to cross it when pressured by systems, authority, or circumstance.

Join me for this week’s Friday Five.

1. What I’m Reading

The Lucifer Effect. By Philip Zimbardo.

Why do good people do terrible things?

It’s a question as old as history. In The Lucifer Effect, social psychologist Philip Zimbardo sets out to answer it.

Zimbardo defines evil as “intentionally behaving in ways that harm, abuse, demean, dehumanise, or destroy innocent others—or using one’s authority and systemic power to encourage or permit others to do so on your behalf.”

In short, evil is knowing better but doing worse.

We fear evil yet are fascinated by it. At Auschwitz-Birkenau and Choeung Ek in Cambodia, I’ve seen for myself what atrocities ordinary people are capable of when ideology grips them.

Zimbardo notes that when individuals in service professions like the police or the army commit illegal or immoral acts, we often blame ‘bad apples’—as though they were rare exceptions. But the ones making that distinction are usually those in charge of maintaining the system—keen to deflect blame away from the leaders who created the environment. Zimbardo argues we should look less at the apples and more at the barrel makers—the ones who design the system itself.

The system often protects itself by pushing moral failure downward—a truth Zimbardo illustrated through his infamous Stanford Prison Experiment in 1971. He recruited students, split them into guards and prisoners, and created a mock prison.

The experiment was supposed to run for two weeks, but Zimbardo ended it after only six days, realising the guards’ abuse of the prisoners had gone too far. The first half of the book is dedicated to replaying and analysing the full experiment.

Zimbardo was shocked at how quickly the students transformed into their assigned roles as guards or prisoners. The ‘guards,’ masked by their uniforms and emboldened by authority, rapidly settled into role-based cruelty. Anonymity was the enabler: the uniforms, mirrored sunglasses, and titles. Once masked, their individual accountability and empathy dissolved, and they acted in ways they never would have before.

The ‘prisoners,’ reduced to four-digit numbers, quickly lost their identities—becoming compliant, demoralised, and in some cases, broken. The experiment showed that systems shape behaviour. And that roles override ethics.

History confirms this. In the 20th century alone, more than 50 million people have been systematically murdered by government orders, willingly carried out by soldiers and civilians. Auschwitz wasn’t staffed by monsters, but by men with jobs, indoctrinated by a seductive ideology that made evil seem moral.

Zimbardo likens morality to a gear in a car. Most of the time it’s engaged: reflecting that most people most of the time are moral. But at times it gets pushed into neutral—disengaged. If the car is on an incline, it moves dangerously downhill. Circumstances—not the driver’s skills or intentions—determine the outcome.

One of the most powerful ways to disengage morality is through dehumanising a potential victim. Language is crucial. A single word—‘animal’—has been shown in studies to change how we see another person. As psychologist Albert Bandura said:

“Our ability to selectively engage and disengage our moral standards... helps explain how people can be barbarically cruel in one moment and compassionate the next.”

We saw this in the Rwanda genocide of the 1990s, where Tutsis were labelled ‘cockroaches’—a word that made their extermination seem justified. In just 100 days, around 800,000 people were slaughtered by Hutus.

Zimbardo’s most powerful argument is that evil is not committed by monsters, but by ordinary people in extraordinary situations. It’s not that ‘some people are just bad’ but that situational forces and systemic pressures are more predictive of behaviour than character.

“The line between good and evil is permeable… and almost anyone can be induced to cross it when pressured by situational forces.”

Those who do evil are not different from us.

They are us.

If that’s an uncomfortable thought, Zimbardo leaves us with a measure of hope. If ordinary people can be made to do evil, they can also be taught to resist it.

That choice is ours—as we will see next.

2. What I’m Watching

Casualties of War (1989). Directed by Brian De Palma.

Casualties of War is one of the lesser-known films about the Vietnam War, yet it is as harrowing as any. The Washington Post called the film, “one of the most punishing, morally complex movies about men at war ever made.” Directed by Brian De Palma, it tells the story of a five-man patrol of American soldiers who abducted, raped, and killed a Vietnamese village girl—with only the fifth soldier objecting and eventually reporting the crime.

The film is based on an actual incident, first reported in The New Yorker by Daniel Lang in October 1969. Lang revealed how the chain of command enabled the atrocity—and then tried to cover it up. The system in full effect.

The film’s two key roles are played by Sean Penn as the sergeant, Meserve, and Michael J. Fox as the new infantryman, Eriksson. Meserve is a charismatic, competent soldier with less than a month to go before returning home. He’s only 21—hardly older than Eriksson—yet vastly more experienced. He is capable of leadership and even heroism (he saves Eriksson’s life in the first act), but he is also the instigator of the film’s terrible central event. He’s effectively the ‘barrel maker’ within the unit—the classic figure Zimbardo warns us about: a confident, even heroic leader who uses his authority to redefine what is permissible.

As he leads his men on a long-range reconnaissance mission, they enter a village and kidnap a young woman to be repeatedly raped over the course of the mission. Meserve doesn’t use words like ‘rape’ or ‘abduction’. He’s already dehumanised her. In his words, she’s there to provide a ‘service’ the men have been denied. Meserve even tells his men the plan the night before. Eriksson doesn’t believe him, or more accurately, doesn’t want to believe him. He makes a pact with the only other soldier who seems disgusted, but when Meserve questions that soldier’s masculinity, he folds—leaving Eriksson as the only voice of resistance, and putting his life in danger.

The film is clever in the way it shows how most of the soldiers don’t drive the atrocity, but nor do they stop it. They tell themselves it’s easier to follow than to resist, and in that choice lies the banality of evil: ordinary men, doing nothing, allowing the worst to happen.

But there is also the banality of heroism: the idea that resistance can be ordinary. Eriksson is that figure. He’s an unremarkable soldier and he’s afraid, but he’s unwilling to surrender his values—or let his gear drop into neutral.

Penn and Fox are both excellent. Penn is raw, violent, contemptible—he has zero empathy for the girl, only rage. It’s easy to see how weaker men bend to his will. Fox plays the good man, the one we’re most likely to identify with, but he is powerless to stop what happens. His values are tested for the first time, in the most extreme environment, in the most extreme way.

The film shows that when a group dynamic like this is at work—especially in a system like the military, with its uniforms, ranks, and the chaos and fog of war—a ‘good’ person can do little to intervene. The girl is dehumanised. She is no longer a girl, but ‘Viet Cong’ (even though she isn’t). It’s a lie easily swallowed. An example of how a single word can flip a switch in the mind: far easier to abduct a member of the brutal enemy than an innocent village girl.

Even when Eriksson reports what happened, the chain of command shows little interest. They don’t bother with the ‘bad apple’ excuse, only words to the effect of ‘Well, this is war, and war gets confusing.’ But Eriksson can’t and won’t let it lie. His own values are too strong. Eventually the case is pursued, and the four soldiers are court-martialled and sentenced to long prison terms.

Eriksson remains haunted.

So do we.

What Zimbardo showed in the laboratory, Casualties of War shows in the field: systems can turn ordinary men, placed in extraordinary situations, into perpetrators of evil—but they can also produce resistance.

While evil may be ordinary, so too can courage.

3. What I’m Contemplating

Philip Zimbardo’s metaphor of morality as a gear is a compelling one. It prompts further questions: what pushes the car onto an incline? When do we lose control of the wheel? And in an age of driverless cars, are we even in charge of the gears anymore?

Most of us will fortunately never be tested in the extreme environments that unmoored morality in places like Nazi Germany. But moral disengagement can take place on a much smaller scale, in everyday life.

It might look like:

Office dynamics: bullying, blame-shifting, taking credit for others’ work.

Group silence in unethical decisions—choosing not to speak up.

Digital pile-ons and anonymous cruelty on social media—the modern equivalent of The Stanford Experiment.

We might ask where in our own lives has the gear been nudged into neutral, and how quickly do we recognise it and shift it back into gear?

Zimbardo’s warning was clear: evil rarely begins with a single leap. It begins with tiny acts, normalised through repetition. Comply once, and you are more likely to comply again—each step a little further down the slope. History is rich with examples.

But the same is true of resistance. Small acts of courage accumulate. Choosing to speak up once makes it easier to do so again. Yes, the gear can slip into neutral—we are only human after all—but it can also be re-engaged.

Ordinary people can resist. Ordinary people can choose differently.

That choice is on us.

4. A Quote to note

“The mind is its own place, and it itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.”

- John Milton, Paradise Lost

5. A Question for you

When was the last time your morality slipped into neutral, and what did you learn from it?

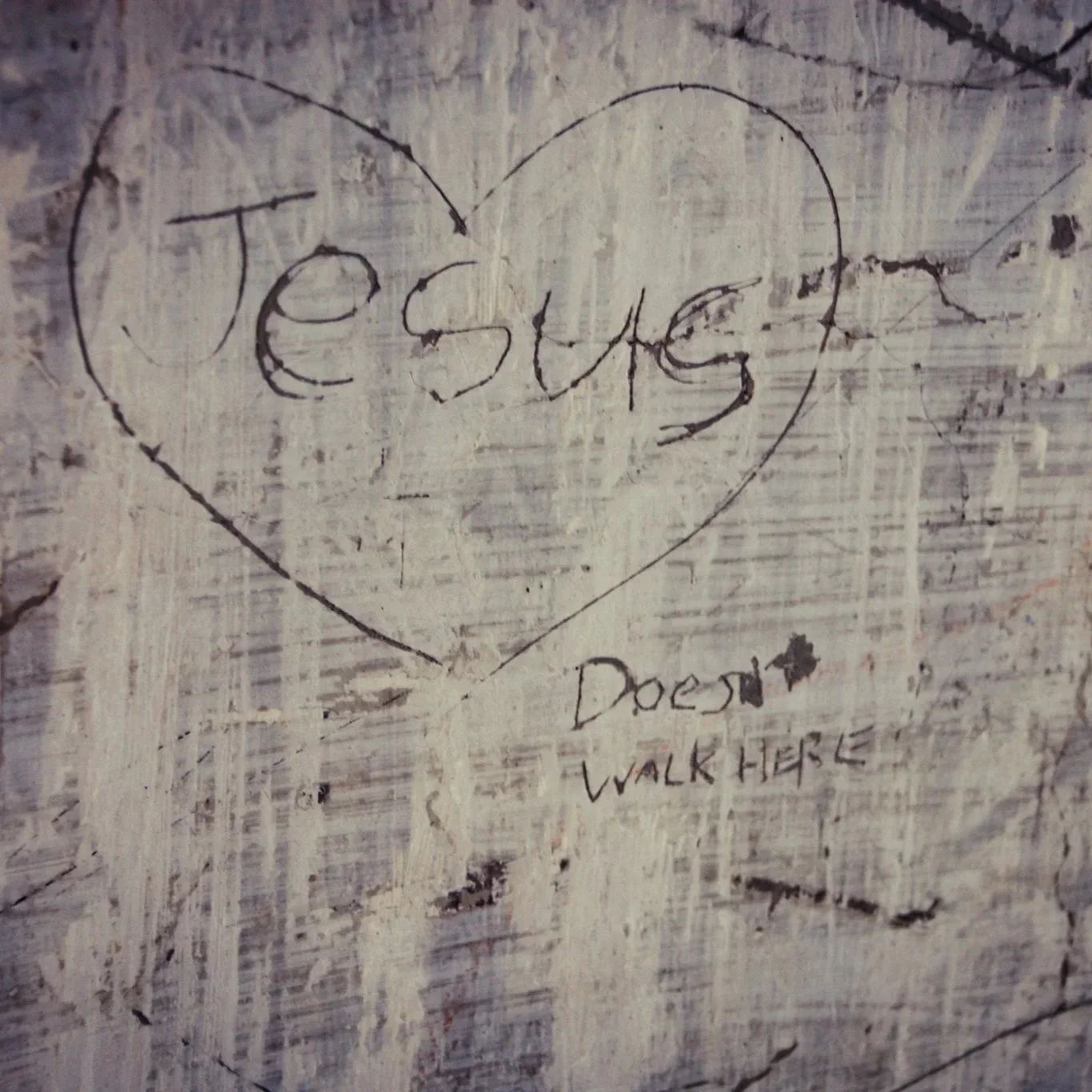

This week’s cover image is a photo I took in 2013 at the S-21 prison in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Once a high school, it was taken over by Pol Pot’s security forces in 1975 and turned into the largest centre of detention and torture in the country. When Phnom Penh was liberated in 1979, only seven prisoners were found alive. Here, in brick and concrete, was Milton’s vision made real.

Thanks for reading and supporting Deep Life Journey. If you have any reflections on this issue, please leave a comment.

Have a great weekend. Stay intentional.

James

Sharing and Helpful Links

Want to share this issue of Deep Life Reflections via text, social media, or email? Just copy and paste this link:

https://www.deeplifejourney.com/deep-life-reflections/august-29-2025

And if you have a friend, family member, or colleague who you think would also enjoy Deep Life Reflections, simply copy, paste and send them this subscription link:

https://www.deeplifejourney.com/subscribe

Don’t forget to check out my website, Deep Life Journey, for full access to all my articles, strategies, coaching, and insights. And you can read all previous issues of Deep Life Reflections here.